Find a sense of purpose, they say. Why? That’s part of it: locating a satisfactory response to the ‘why?!’ that pulses at our cores. Why are we doing this? Waking up, eating toast? Putting on work shoes and freshly laundered clothes, ordering things, spinning through our hours like socks in the washing machine, around and around, the days, the hours, the ceaseless wash of ‘why’ in the mind.

To lack a purpose seems embarrassing, like a constitutional nakedness. We are supposed to know, somehow, why we are on earth, why we are trying to do anything productive with our lives, and even what that specific productivity is supposed to entail. We are supposed to identify, as early and ardently as possible, what it is we care most about and can pour best our existential passion into; we are supposed to possess headings, goals, a driving motivation that directs and explains how we live our lives.

Purpose, however, often remains elusive. I’ve begun to think it isn’t always a helpful organizational principle around which to build a life. Not, to the contrary, that we should all waver purposelessly in random winds of chance, but, perhaps, that putting less of a burden on ourselves to ‘find’ and ‘pursue’ a purpose, as though the fire that lights our lives is also an animal of prey hiding in the bushes, may be more nourishing in the long run. It’s possible you do not have a central purpose; it’s plausible you have many, and that these purposes may change and grow along with you. It’s possible that a call to purpose motivates us to accomplish amazing things, but that the endeavor to simply live well may be purpose enough.

For the theme of purpose, we have here a motley collection of books, some about characters driven by a singular, urgent aim, others about navigating apparent purposelessness.

6 DETERMINED BOOKS ABOUT PURPOSE

| Title | What stands out | Read this when | |

| Joan by Katherine J. Chen BUY INDIE | In this reimagining of Joan of Arc’s life, Chen shows us an adamantine tomboy forging her own path forward, for better or worse. It’s an intriguing portrait of an immensely purposeful warrior woman. | You want something to lift your chin. | |

| Mankiller: A Chief and Her People by Wilma Mankiller BUY INDIE | The first elected female chief of the Cherokee Nation, Mankiller’s memoir brims with purpose as she details influential legislation, personal moments, and native stories to show us what’s happened and what should change. | You haven’t read enough about Native leaders. | |

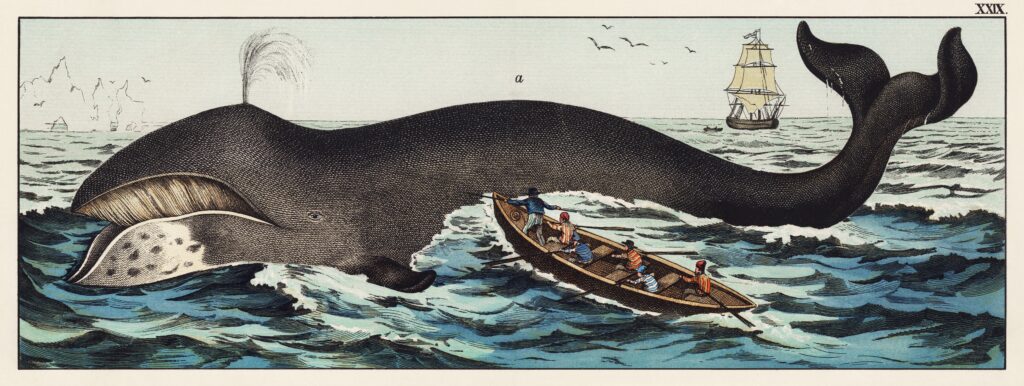

| Moby Dick by Herman Melville BUY INDIE | Yes, it’s the book you see recommended everywhere, surfacing here yet once again. Because. It’s subversively funny; it’s passionate; it’s not afraid to muck about with whale details for page after salty page. Because Melville is having so much fun here, and because Ahab is nothing if not maniacal. | You run up your sails for big stories crammed with tangents and delightful asides. | |

| Honouring High Places by Junko Tabei BUY INDIE | Through fortitude and a drive to experience nature, Tabei has seen places few of us will ever set foot in. We can be grateful, then, for her memoir on mountaineering and encouraging others to seek out nature as well. | You feel moved by people who dare to do unusual things. | |

| Behave by Robert M. Sapolsky BUY INDIE | Do we always know why we do what we do? Not so much. So it’s welcome to encounter a book that carefully dissects some of the science behind our actions. | You’re ready to look under the hood of being human. | |

| Found: A Life in Mountain Rescue by Bree Loewen BUY INDIE | Loewen’s dedication is inspiring, but it’s also worth examining her motivation and why it proves so difficult for her to find professional footing. | You wonder about heroism and what it takes to do hard, cold work in the night |

Feel heroic with Joan by Katherine J. Chen

The narrative swing of Joan of Arc’s life is breathtakingly brief. She was filled with purpose by 13, introduced to the French court by 16, leading France’s army and military strategy by 17, then burned at the stake by 19.

She is a character shaped by gripping times, living at a period when, as * points out, religious revelation was one of the only ways available to alter court policy or the trajectory of a country. In an era in which monarchical heredity was how power usually got consolidated, it’s strange indeed that a 16-year-old village girl calling herself the “Maid of France,” who was unable to even read or write, inspired enough devotion steered an entire nation onto a new course.

Joan by Katherine J. Chen

The strangeness continues today, since Joan’s burnish has yet to wear off. Whether it is her diamond-sharp sense of purpose that draws us or the sheer unlikeliness of her narrative, we remain fascinated. Reviled by many when she died, Joan was declared a saint 500 years later. Today she is the saint of France’s army and, indeed, the entire country. She has been claimed as a symbolic figure by Catholics, Fascists, far-righters and feminists; she has inspired numerous books, video games, comic books, films, and even two rock operas (yes, two).

We still aren’t sure if her purpose arose internally, some novel but adamantine seed she somehow carried to fruition, or if her purposiveness stemmed from a mental condition such as schizophrenia. No matter now, perhaps. She heard the voices of God and of St. Michael; she saw bright lights; she made it, somehow, to the highest court of her country, carried a banner in the name of King Charles VII, and prevailed against the invading English. She was captured, tried for claiming to talk to God and for wearing men’s armor, and subsequently burned.

“In seeking the answer, Chen will have faced a dilemma familiar to historical novelists: to privilege the recorded history of Joan, which shows her as the instrument of God and men, or to acknowledge the expectations of modern readers, honed by stories in which a woman can be the agent of her own life rather than the object of others.” The Guardian

In Chen’s account of Joan’s life, vengeance rather than religious conviction motivates France’s young heroine. As Chen would have her, Joan was a muscular powerhouse, a tough-tumbling tomboy able to survive beatings, navigate court politics, and wield a longbow without fault. Chen’s Joan is an individualist, comfortable in a contemporary way with “being herself,” “raising her voice,” and otherwise achieving redemptive purpose in the pursuit of her own aims according to her own character.

“You must make your own map of the world. Search out your own piece of sky and patch of earth, your own awning to sleep under when it is raining and it feels the sun may never shine again, for there will certainly be such days. No one can walk this path for you. You cannot simply follow in another’s footsteps, as though life were a complicated dance, every turn and twist memorized and prepared for ahead of time. There are many things in the world you can inherit: money, land, power, a crown. But an adventure is not one of them; you must make your own journey.”

This is not the Joan we know from the historical account, who by her own words was much more compelled by her conviction that God meant her to unite a country than she was whatever happened in her village.

“I firmly believe, as firmly as I believe the Christian faith and that God has redeemed us from the pains of Hell, that the voice comes from God and at his bidding.”

joan of arc

Chen’s narrative then serves as a sort of meta-interrogation of purpose itself, asking what purpose story serves, then as now. Have our tastes changed? Do we find it so unpalatable or so unconvincing, that God might speak to a girl, or that religious mania changed the course of history, that we prefer our heroine to run on the fuel of a contemporary understanding of trauma? Are we so in need of historical hope and the encouragement to be gleaned from the possibility that one of history’s leading figures was guided by her own confidence and own ability to wrest choice and power away from the monarchical patriarchy, that we find ourselves willing to strip away much of the story’ historical context, the gullibility of leading figures, the desperation of a deposed king, the political power of an unlikely figurehead, the pawn-like purpose she may have served at the time and later surmounted through narrative appeal to greater aims?

I find these questions fascinating; I find the choices authors make to tell us much about ourselves. In our literature as in our lives, I think, we follow *’s principle: we see what we wish or have been trained to see. We see what, in broad terms, our particular culture sees. We see the steeliness of Joan and the survival instinct whereas a contemporary of hers in 1400s France might perceive purity of spirit.

“One life is all we have and we live it as we believe in living it. But to sacrifice what you are and to live without belief, that is a fate more terrible than dying.”

Joan of Arc

Today we might not rally behind someone claiming to be receiving religious revelations. We might choose to follow a Greta Thunberg* instead or a *, someone whose youth and strength of will adopts a narrative shape we are prepared to understand and find appealing. We might resonate with the feminine power Chen portrays more than the preoccupation with God she omits. What does that mean? What does it imply, that we are tempted to continually reinterpret our heroes and myths for alternate possibilities, and how does it help us, as readers, to play with these possibilities?

Much like Margaret Circe’s* reinterpretations of Greek myth, historic retellings can feel like opening windows in a creaking old barn to let in fresh air. Who knows if the retellings are true? If it’s “fair” to twist and retell, like turning a kaleidoscope to find a different pattern. But it’s fun; it’s invigorating; it’s like throwing dice, seeing what permutations tumble to the surface, what universalities continue to call us. And it brings new voices to light or at least amplifies whispers that might have been there all along, going relatively unnoticed. The practice of retelling lets us invite ourselves into the past, where we can untether our imagination and let it run ruckus.

Retelling teaches us to seek alternate possibilities in our own lives, and trains us in the playful but essential practice of refusing to be walled up in the predominant narrative, which over time can become a dogma. After all, you can try to burn a story at a stake. You cannot control, however, what shapes the ensuing smoke takes, how long it lingers or how far it drifts. A person may die, but not a good story–a good story serves many purposes.

Where’s the bibliography?

It’s likely you will see what you need to in Joan’s story. Maybe it’s her determination that calls you; maybe it’s her eloquence even when facing the fire. Like a shell held to your ear, see what you perceive in her story.

For me, I take inspiration from Joan’s ability to proceed without a blueprint. Who was she, to command entire forces and to flaunt her weird, God-given purpose? Absurd. I suspect I would not actually like her in person; I suspect I would feel thrown by the symbolic power a single person can wield (and lose) so sweepingly. Yet look how she threw herself into history; look how she rode the white waters of time. Look how, even if God was not truly thundering in her mind, she convinced herself to stick fast to a tricky and uncharted course. Look how uncanny it is, to practice conviction.

A little more

- Joan has been featured in an off-Broadway play, “Into the Fire,” by David Byrne

- Bone up on Middle Eastern female warriors in Pardis Mahdavi’s book, “Book of Queens”

- Listen to the Arcade Fire song

Watch a chief spread her wings with Mankiller: A Chief and Her People by Wilma Mankiller

We turn now to a woman who broke another gender barrier: Wilma Mankiller, who became the first elected female chief of the Cherokee Nation. Writing in her own words, Mankiller believes it essential to include the broader narrative that informs her own story, so she includes much of what has been happening to the Cherokee within the past several hundred years.

“One of the things my parents taught me, and I’ll always be grateful as a gift, is to not ever let anybody else define me; that for me to define myself . . . and I think that helped me a lot in assuming a leadership position.”

Mankiller: A Chief and Her People by Wilma Mankiller

One reason for Mankiller’s success could be that her purposes did not entail advancing her own agenda or raising her own profile. Instead, she worked steadily, little by little, to support her people. One element I appreciate is how her narrative is not one of abrupt leaps and of perfectly polished progression, but is more realistic and therefore, I think more inspiring. She shows the amount of heart it takes to keep doing repetitive, non-glamorous things until those things add up over time. In a culture that emphasizes near-overnight success achieved on one’s own terms and generally tailored to serve only oneself or one’s immediate family, Mankiller demonstrates a way to embrace one’s values and community in a broader, more grounded way.

Where’s the bibliography?

So very many times, we get the narrative of the invincible hero who shows up just in time, having completed a few training montages, and then handily vanquishes all assailants. Rarely do we see heroes struggle, including with their own community and their own nature. For me at least, it helps to encounter a human-sized hero who doesn’t glamourize the difficulty and the patience it takes to create a real difference. Mankiller also highlights how her sense of purpose kept her moving forward, reaffirming her sense of self as long as she acted in the interest of others.

A little more

- Wilma Mankiller’s biography

- NPR posted a story on Wilma Mankiller’s work

- Watch The Cherokee Word for Water, about Wilma Mankiller’s work bringing running water to her tribe

Embark on an epic classic with Moby Dick by Herman Melville

Maybe it’s in vogue to be defensive about liking Moby Dick? Oh well. It is bloated and it is overblown; I’ll give you that. But it’s that way only because it’s also so joyful; it’s ridiculous because perhaps it’s a little ridiculous to love words and to glory in them as much as Melville does. I mean, can you resist the beginning?

“Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul; whenever I find myself involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet; and especially whenever my hypos get such an upper hand of me, that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping into the street, and methodically knocking people’s hats off – then, I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can.”

I can’t; I can resist very little about this book. Who knows his exact purpose in writing this salty epic–whatever he intended, this was a commercial flop, a let-down, his critics averred, because it was neither a philosophical disquietation, nor a straightforward adventure story about whales. It is nothing more or less than a shaggy whale story, drifting all over, and thus somewhat purposeless-seeming. Yet, give it as close a read as a tumbler of peaty whiskey and an impending bedtime will permit (this is not a morning-time book), and you’ll find yourself hot on the trail of all kinds of purpose.

Moby Dick by Herman Melville

There is, of course, the purpose I don’t even have to tell you about, the one-legged, bloviating revenge story served salty and cold and grim. There is the obvious moralizing and allegorizing, and there are the more subsumed forms of symbolism, too. There is Melville’s inability to resist a good, meaty fact – or a whole shoal of them – and there is his ludicrous, endearing habit of pell-melling off on all sorts of tangents. He will take an idea, beat it to the bone, then–squirrel! (or, as it were, white whale!) dash off in a different direction altogether. There is all the Biblical allusion, heaped up like fish guts, and there is the portentous language, which seems to be Melville playing at literary Jenga, piling up phrases until a crash seems inevitable.

There is the sly and outrageous humor winking at you from every corner. Though I believe Melville is deadly serious at hinting that men are more equal than it was morally relevant to claim in his lifetime, and that God is lost at sea or altogether imaginary, he doesn’t let the agnostic cynicism stop him from ramming in a good joke. Neither does it stop him from his own form of sermonizing, a cantankerous blend of caution and wit and allusionary silliness, mixed with trivia and anchored with philosophical weightiness.

“There are certain queer times and occasions in this strange mixed affair we call life when a man takes this whole universe for a vast practical joke, though the wit thereof he but dimly discerns, and more than suspects that the joke is at nobody’s expense but his own.”

I suppose where this book hits me is in the gut. Not least for its treatment of life’s sudden turns or its focus on the apparent futility of tilting at white whale (or, in other words, grand passions), but also for its unapologetic examination of what it means to live. Despite how much he scribbled out, Melville was no desk jockey of a writer. I suspect his desk was at time more likely to be a crowsnest or rock on a deserted island. Many of the maritime episodes he mentions are ones he experienced directly or possesses first-hand knowledge of. He himself whaled, was marooned, lived with islanders, and more, a life of half-jobs and strange pursuits, escapes and adventures, big gambles and long stretches of being overlooked.

For those of us who cannot seem to settle down, either internally or externally, he is a kindred spirit. Simply knowing about him is comforting, seeing as he possessed so many chances to capitalize on his privileges and live the life of a country gentleman. Instead, a review of his life has him racing about, pursuing first one thing and then another, much as his writing proceeds. It seems difficult for him to resign himself to any one pursuit.

He is not comfortable on the earth and perhaps only slightly more so on the high seas. This helps me a lot, actually, seeing as it can sometimes be so hard to pick a direction in life. I take it as consolation that one’s deeds may live on, little as they may be recognized in one’s life. I take consolation, too, in reflecting that a life such as Melville’s may not (as judged during his lifetime) have contained much of clear worth, but that he did, in fact, live richly and intensely, both on and off the page. He may not always have known his purpose, but his work vividly illustrates the art of trying, anyway.

Where’s the bibliography?

It’s tough to say anything original about Melville or Moby Dick. So you can chase down thread after thread about him, critique after critique. Whole post-graduate careers have been founded on his work, after all. You may wish to search out your own resonance with him yourself.

Or, like me, you may wish to seek solace in Melville’s use of vividness. This book, after all, is an exceedingly odd pastiche of literary techniques, some of which were barely developed in his day. Imagine how strange it had to be to read him back then, if even today his style strikes us as so experimental. Read him for the hints of queerness; read him for his vicious descriptions. Read him to see his narrator unloosed, let free to wander through science, philosophy, and whale foam. Read him to see his own self-acceptance at play, a grand writer declining to play by polite literary rules or to muzzle his own exuberance.

When I find myself heading into a personal November of the soul, I turn to Moby Dick to help lift the fogs a bit. Melville is neither cozy nor reassuring, but he is gloriously deadpan and overweeningly verbose, and by the time you make it through all those many hundreds of pages, you may also have reached your own personal April, a stormy but spring-like time when you can let yourself feel more alive and less repressed, more about to bloom.

A little more

- Not up to reading this tome yourself? Let celebrities read it to you instead

- Odd facts about Melville

- About the queerness in Moby Dick…

Get a taste of mountain time with Honouring High Places by Junko Tabei

Honouring High Places by Junko Tabei

Relentlessly mocked for being diminutive, Tabei ended up summiting some of the world’s highest peaks. That’s already a gripping achievement in and of itself. Read deeper into her story, however, and you’ll encounter a woman whose strength and sense of purpose comes not just from how to feels to reach one’s physical dreams, but also from her determination to introduce others to mountaineering while also promoting conservation. For Tabei, it doesn’t get much better than being outdoors, preferably with excellent company, inching up an icy slope. A climber well into her seventies, Tabei never lost sight of the joy of ushering others into the presence of mountains as well. From summiting Everest alongside her female sherpa to encouraging children to help clean up mountains, Tabei let her love of the world’s highest places shape her purpose. I love her story because it springs not from suffering but from the wish to help others feel more confident and inspired as well.

Where’s the bibliography?

Perhaps you, too, feel small in the face of what you’d like to do. Maybe others say you can’t accomplish it or maybe you feel embarrassed about how much you love this particular pursuit. Can you take a page from Tabei and let your love carry you onward? You don’t have to see the exact destination ahead of time to start walking toward it today.

A little more

- Watch an animation of Junko Tabei’s remarkable life from Little Fox

- Read Outside Magazine’s interview with Junko shortly before she died

- Watch the film Sherpa about these incredible mountaineering people

Learn why we do what we do with Behave by Robert M. Sapolsky

To have a purpose, it’s useful to understand ourselves and how we think. Cue Sapolsky and his big, wide-ranging, interdisciplinary book to crack open human cognition and give us reasons for why we do so much of what we do. For those of us who scratch our heads over human behavior, this is a useful manual that can prompt a little more slowness and thoughtfulness. It comes with a few caveats – in a book this sprawling, for example, not all the details may be borne out by advancements in science–but overall, it’s a good overall read that collects much of modern neuroscience into one place and bundles it for easier consumption. It also takes substantial stabs at answering looming questions such as Why are we so violent? Why do we so often fall into “us vs. them” thinking? Why is it so difficult to control ourselves when we feel gripped by extremely strong emotions? What influences our decision-making, biologically speaking?

Behave by Robert M. Sapolsky

Where’s the bibliography?

Maybe you already know your purpose and what drives you. Maybe you’re still figuring that out. Or maybe you’re trying to glimpse what drives others and what purposes they’re pursuing. If the latter is true, Sapolsky’s explanations will likely prove illuminating. (They’ll also give you excellent nuggets to fuel dinner-table conversations).

“by the time you finish this book, you’ll see that it actually makes no sense to distinguish between aspects of a behavior that are “biological” and those that would be described as, say, “psychological” or “cultural.” Utterly intertwined.”

A little more

- Robert Sapolsky talks to Amy Parish

- Have less than a minute for this massive book? Get the under-a-minute version from IdeasInHat

- Much of Sapolsky’s work has been involved with baboons…why not watch some baboons enjoying honey?

Interrogate purpose with Found: A Life in Mountain Rescue by Bree Loewen

Alright, so this post has heavily featured mountains, hasn’t it? (If you must know, even Melville was obsessed with the mountain he viewed from his study window as he composed Moby Dick–he, of course, thought it resembled a whale’s great, gray fin.) We don’t cease our mountain bent with this last selection, Loewen’s affecting and sometimes frustrating account of serving as volunteer mountain rescue member.

Mountains are easy metaphors when discussing a sense of purpose. They command our attention, refuse to be ignored, and give us clear, icy targets upon which to hone our sense of purpose. Clamp on your ice spikes, seize your piton, and head for the place the oxygen gets thin – a mountain, if it is high and imposing enough, sets you free from the rest of the world, both because it suspends you so far about regular affairs, and because it makes you feel ennobled, dedicated to a distinct purpose, and way above the dusty fray.

Perhaps Loewen’s problem was that her mountains were the Cascades, which are certainly lovely enough, but which do not exactly possess the gravitas of the Alps, the Andes, or the Himalayas. The Cascades are backyard mountains, at least the sections Loewen regularly traversed during rescues, and they are low and close enough to lure city folk into pursuits that seem safe as playground slides, but often end up proving perilous.

First, my biases: I was raised much as Loewen was, both in the sense of being homeschooled and in the sense of spending many formative years in and around the Cascades. Though I was not a member of her mountain rescue group, some of my friends were. And though I was not a dirtbagger chasing free solos through the foothills, I, too, spent the bulk of the weekends climbing and hiking in the areas she highlights, (and I, too, considered becoming a paramedic in King County). So in some ways, this book feels familiar. In other ways, perhaps because it is so very close to home for me, it aggravates.

Found: A Life in Mountain Rescue

by Bree Loewen

I’m including it because Loewen is so honest, honest, in a way, I think, that includes being inadvertently honest about her own areas of obliviousness. So her reflections on mountain living and mountain rescues come across as refreshingly intense at the same time they are sometimes numbingly bewildering.

Why, the reader wonders, does she so frequently drop everything, including her toddler, to gallop up into the muddy hillsides during blinding rainstorms? To rescue others, the answer seems to be. Duh. But so often the unfortunate adventurer she wants to rescue is already known to be dead, or is highly likely to be dead, and so it becomes a little baffling to witness, time after time, how willing Loewen is to, in effect, block many aspects of her own life to walk a body out of the woods. She doesn’t herself seem quite sure why she’s doing it. She hopes, I think, that her dedication and mere presence lends a certain degree of support; she does it because she would want someone else to walk her body out, if it came to that.

Fair enough. Yet the rescuers risk their own lives far more often and profoundly than Loewen seems comfortable addressing (and the slip-ups she does mention are concerning enough). They lack a central depot where they can store their equipment; they are underfunded, struggling to provide trainings and to supply themselves with good-enough gear. And when they do have the gear, they spend hour upon hour waiting, slogging up and down mountains and slopes, schlepping that gear or trying to find each other. They wait for others to arrive, for equipment to be located, for the weather to clear, for the coffee to be brewed. I know I’m coming across as irritable now – after all, they are doing vital work; they are undoubtedly saving folks, and so who cares if at times they seem disorganized or rag-tag; who cares if that’s how they’re spending their time (and what do I know about running a mountain rescue anyway?), because aren’t there so many worse ways to spend that time?

There are indeed. For Loewen, it seems to be a struggle to do anything other than answer rescue calls. Yes, she has a toddler and a husband (he competes so badly with her, they can’t work much together); she has ambitions to get a “real” job, to leave volunteering in order to earn money and claim a place in the world of professionals. Professionals, it turns out, rub Loewen the wrong way. She already knows so much about the outdoors and about emergency situations and how to command disparate teams, but she also struggles to leverage this expertise into “the next thing,” whether that be nursing, becoming a paramedic, or focusing on mothering.

It’s hard, in Loewen’s mind, to stop trying to tick off a few indicators of societal “success;” it’s also hard to stop answering emergency calls. For me, her memoir is a testament to uncertainty, to being afraid of what you’ll lose by moving forward, and to the bitterness of being unrecognized. It’s a book about getting in your own way; it’s also a vivid illustration of how important companionship and respect is. It’s a book, ultimately, about meaning. For Loewen, meaning lies in keeping her friendships strong and in doing urgent things during bad weather together. She, I think, would approve of Primo Levi’s attitude toward outdoor adventures, that it’s sometimes the bad ones that are more memorable, and that, to truly be an outdoorsperson, you need to eat a little “bear meat” now and then.

Yet Loewen doesn’t conceal how many times she has to ask others to pick up the slack for her so she can do this, and she doesn’t softpedal the rigors of trying to rescue others when you yourself are floundering. When I volunteered on a midnight crisis line, I saw much the same: by no means were those of us answering the phones the most composed or put-together individuals out there.

And maybe that’s the point; maybe those of us who feel bitten by uncertainty and frustrated by a lack of progress do well to find friends and to help others, even if it comes at a high and sometimes undermining cost. Maybe not. Reading Loewen, I suspect, you’ll have to determine that for yourself. In any case, you’ll encounter an author clearly driven by both intensity and the desire to immerse herself in a wild life. If I’m honest, this book made me jealous, just as much as it sometimes frustrated me with its single mindedness.

Where’s the bibliography?

This book was like of those great friends who both madden and inspire you. I found myself envying Loewen’s drive and the huge cache of adventure stories and rescues she’s now amassed. I resonated with the complicated grief of needing to give up something you care about; I felt for her, such was the intensity of the friendships she built along with the deep expertise she can now claim.

But I also wanted to shake her and ban her from answering at least 60% of the calls she was doing, because she does, in my opinion, need to focus more on her own aims. She can’t seem to escape the adrenalin rush and perceived urgency of saving yet another lost adventurer, but the way she tells her story, that adrenalin buzz also helps obscure how tired she must be and how much the mountains are taking from her. How long can she keep it up, you end up wondering. Will she let go a bit, take care of herself, and invest the steady, not-so-adrenalin-filled work that helps her channel her drive to care into easy that will reach more people over the long run?

Hers is one of the strongest testaments I’ve read to the power of needing to help others. It can become its own addiction, and the black humor and relationships with colleagues you develop along the way, I know, can feel so much more important than the dull mundanity of the rest of life. But get in too deep, and the culture of being heroic can carry you away. Just as insistently as an avalanche (though much more slowly), it can sap your life and isolate you from others. So if you’re likewise feeling caught in the undertow of giving perhaps too much of yourself, this could be a therapeutic read, a kind of gut check, if you will. It could also function as a call to live a deeper, riskier, more sacrificial life.

A little more

- Learn more Seattle Mountain Rescue (and consider supporting them)

- Absorb useful hiking tips from the National Parks Service

- Planning a Washington State hike? Get amazing trail guides online from Washington Trails Association

- Can’t get enough of mountain writing? Listen to Bree Loewen talk to Tommy Caldwell