6 THRILLINGLY INTENSE BOOKS

Neither consistently positive nor negative, intensity can imbue our lives with electric meanings. it can be addictive; it can make us search and marvel; it can, at the very least, spray a bland afternoon with neon.

| Title | What stands out | Read this when | |

| Equus by Peter Shaffer BUY INDIE | What I liked here was how Shaffer lets his main character become “strange,” inventing his own rituals to counter a claustrophobic dominant narrative. It may not work out, but it does ask where we are to get a sense of wildness and deep connection with the unknown. | You’d like to fall into a different, somewhat akimbo mind determined to be as alive as possible. | |

| Weep Not, My Wanton by Maggie Dubris BUY INDIE | Dubris layers stories of being a NYC paramedic with poems, scraps, and more to construct a collage that contemplates unwritten rules, demanding expectations, and the odd beauties of a job spent trying to reach out. | You like hard, lyrical language about the things and people often shoved to the shadows. | |

| Infinite Powers by Steven Strogatz BUY INDIE | Calculus intense? Intensely demanding for some, yes, and also intensely interesting in this explanation of how infinity came to be as a concept we cannot fully comprehend, yet which deeply influences our lives. | You want to waltz with the concepts numbers and formulas represent. | |

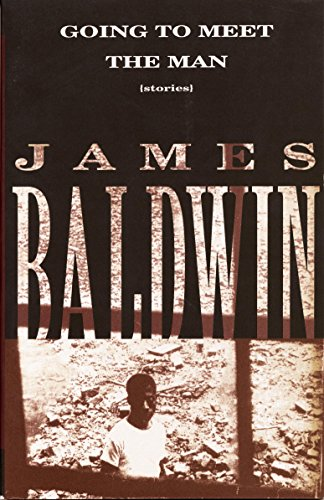

| Going to Meet the Man by James Baldwin BUY INDIE | In these short stories, Baldwin is working out many of his trademark themes, slowly ratcheting up the intensity of his concern for ethical dilemmas, moral murk, and complicated feelings. | You’d like your intensity in smaller doses. | |

| Untold Night and Day by Bae Suah BUY INDIE | A walk through Seoul becomes increasingly surreal in this novel from Suah, where fact and fiction blend in an uneasy reflection of how quickly we can lose track of what’s “real” and what is merely perception. | It’s all a haze. | |

| The Moviegoer by Walker Percy BUY INDIE | Some accuse Percy’s main character of ennui or over-privilege. Yes, to an extent, but I’m also caught by the depiction of someone unwilling to enter a pre-planned life, who dallies, yes, but also tries to devise his own ways to experience the world. | Your apparent dreaminess hides an intense inner life. |

How Peter Shaffer’s Equus weirdly thrills

Not even a proper book, but a play, Equus is brief the way a fired bullet is brief. Though some may perceive traces of naivete or sensationalism in Shaffer’s masterwork, it still smolders on stages to this day.

It may best be read in private, however, where you can appreciate the depth of the intensity. Shaffer based the play on an actual occurrence, wondering what could possibly undergird an inciting incident of such bizarre violence. In his wondering, he unfolds multiple motivations that can be easier to absorb on the page than the stage.

Equus by Peter Shaffer

This is not, I should say, a book for those who become queasy easily or who are uncomfortable with the stranger recesses of the soul. It does, however, becoming gripping as you watch its narrator, a dry psychologist, wonder with mounting unease whether quelling every chaotic yet deeply felt impulse is appropriate.

This is a book, in other words, about a professional doubting his profession just as much as it is an interrogation of intensity. Shaffer’s depictions of doubt and of strange ritual brush against the alarming flanks of intensity, the places where coals and sparks threaten to flare into conflagrations. Society likes its citizens to behave predictably, it’s tough to weed out the intensity going on even behind your neighbor’s door or maybe even inside your own home.

Is conformity, Equus asks, worth the price it exacts? When is it too dangerous or too self-involved to privilege the emotional pleasures of intensity? As the narrator wrestles with whether he is helping or hurting his client, we are prompted to question our own assumptions. Do our religious beliefs give us enough leeway to be ourselves? Should we prioritize individual passions over societal norms?

“The Normal is the good smile in a child’s eyes:-alright. It is also the dead stare in a million adults. It both sustains and kills-like a god. It is the Ordinary made beautiful: it is also the Average made lethal. The Normal is the indispensable, murderous God of Health, and I am his priest. My tools are very delicate. My compassion is honest. I have honestly assisted children in this room. I have talked away terrors and relieved many agonies. But also-beyond question-I have cut from the parts of individuality repugnant to this god, in both his aspects. Parts sacred to rarer and more wonderful gods. And at what length…Sacrifices to Zeus took at the most, surely, sixty seconds each. Sacrifices to the Normal can take as long as sixty months.”

While it’s tired at this point to portray Christianity and its conventional opposition to sexual curiosity as a given, I forgive the play some of its more clunky psychosocial underpinnings in favor of focusing on the rare and esoteric jubilation it shows.

Equus resonates with me because I can empathize with the psychologist’s restless self-doubt and troubling jealousy. While I’ve consciously and consistently chosen roles that let me observe or perhaps support others as they heal, I, too, am sometimes envious. I wonder how it might feel to feel subject to fewer constraints; I wonder about what might happen if I let myself follow my most unconventional urges. What would it feel like to enter the territory of intense ritual, of glass and blood and iron, heated metal and crackling fur?

When you live a composed and deliberate life, you risk the chance of being left out of life’s weird, liberating, inexplicable dimensions. What if, Equus asks, you never get to sink your teeth into your own wildness?

Where’s the bibliography?

Thanks to the lovely way reading engenders multiple meanings, there are many ways to read a book like Equus. We can be struck by the strangeness, even shocked; we can use the text as a way to stretch how we understand being human. I have benefited from this book, not only from musing along with the narrator, but also from witnessing an author dig into personalized mythology and ritual in a way that doesn’t minimize these private attempts to celebrate and make sense of the world.

A little more

- Proceed carefully, but if intense, thoughtfully made documentaries about the borders of human existence interest you, consider Zoo

- If fictional movies are better for you, Cronenberg’s Crash might do

- You could also read the poetry of Frank Stanford, a master of intensity, in The Light the Dead See

Sob along with Weep Not, My Wanton by Maggie Dubris

I want this book to get more attention. An account of her early years as a New York paramedic, Weep Not, My Wanton lights itself up with a mixture of combustible prose and raw acceptance. It’s wrenching in some of the best ways, an account of dealing with difficult situations while being a little messed up oneself.

Weep Not, My Wanton by Maggie Dubris

Dubris’s willingness to throw herself in among convoluted cases of neglect and human suffering collapses some of the narratorial barriers that often stand between the suffering of “others” and the supposed objectivity of the writer. Instead, Dubris puts the pus and uncertainty right on the page, even managing to wedge in some sardonic humor as well.

Written in lush, nearly hallucinatory language, her account includes lyric poems and drawings. While she could milk her stories for shock value, she displays a pragmatic acceptance and curiosity instead. Here they are, the book lays out, grotesque, perhaps, but still part of life. Just another twist in the braid of intricacies that make up a paramedic’s day.

Where’s the bibliography?

I read this book when I want to be reminded that none of us is actually that separate from people we often allow ourselves to ‘other’ or to overlook. I read it, too, to admire how a writer can channel intensity when empathy is on the line as well. Dubris serves as an illustration of how to care without becoming completely absorbed into the labyrinth of human muckiness while also refusing to become so hardened the details stop sticking.

A little more

- Maggie Dubris’s website

- The Robert Greene poem “Weep Not My Wanton”

- For more ambulance-based intensity, read Denis Johnson’s Jesus’ Son

Let Infinite Powers by Steven Strogatz take you in loops

Who gets excited about math? Steven Strogatz, that’s who. And fortunately for us readers, his passion is infectious. You may not exactly catch math fever, but you may reconcile yourself to a topic that gives many people hives.

Strogatz shows us math as another language, one that continues to shape our lived realities even if we remain oblivious to its workings. Why continue in that state, he asks, when it’s possible, with a little guidance, to more deeply comprehend this figurative force?

Like many, the depths of calculus has continued to elude me, though I have enjoyed shallower sojourns in more readily apprehendable branches of mathematics. So I’m grateful for Strogatz’s passion, which shows us how an intense love for a topic drives us to help others understand it as well.

Infinite Powers by Steven Strogatz

It’s big-hearted, in other words, to make a seemingly obscure topic more comprehensible, and it exemplifies knowledge-sharing as a way to build community rather than to hoard power.

Strogatz focuses specifically on the concept of infinity and how it has driven crucial equations throughout history. Infinity, of course, as an idea has stayed cloistered in academia, and so it proves a useful beacon to help light the passageways of advanced math.

“Infinity lies at the heart of so many of our dreams and fears and unanswerable questions: How big is the universe? How long is forever? How powerful is God? In every branch of human thought, from religion and philosophy to science and mathematics, infinity has befuddled the world’s finest minds for thousands of years. It has been banished, outlawed, and shunned. It’s always been a dangerous idea.”

I admire it for investigating the intensity of a discipline, thereby showing us how powerful ideas humming along beneath the substrate of everyday life shape our world. It is also, of course, an ode to falling in love with ideas and for dedicating one’s life to quietly, yet intensely, exploring these ideas without knowing where they might lead.

Where’s the bibliography?

Intensity isn’t only a marker of unbalance or “weirdness” – it can be a richly immersive and stimulating state, too. In our books and films, we often depict intensity as akin to dysfunction, the provenance of addiction, unbalanced moods, hormonal passions. What about its generative spin though, its ability to guide us toward driving purpose? The electricity of intensity can pull us toward the things that can serve as keels and compasses. If you could get super intense about something, what would that be?

A little more

- Emily Riehl explains infinity in 5 different ways

- Steven Strogatz’s website

- Watch The Man Who Knew Infinity about the mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan

Savor the intensity of Going to Meet the Man by James Baldwin

For phosphorescent prose, read the best of James Baldwin. As he puts it, “There are so many ways to tell the truth.”

One of those ways, which he employs to great effect, is to describe how we infuse everyday life with emotional intensity. It’s not only events themselves that color our days and thoughts, but our reactions to these events and the neurotransmitters that fire into action following these events.

Going to Meet the Man by James Baldwin

With Baldwin, there is much to choose from. You could start with these short stories, for one, since they showcase his artistic intensity in bite-sized pieces that still deliver much to reflect upon. From there you can expand into classics such as Giovanni’s Room. You can notice, over his body of work, how Baldwin excels in melding emotional and cognitive intensity while still contextualizing them within a larger societal structure. His characters are never separate from social forces; his scenes are driven both by sensory intensity and by tracking down the implications of these sensations.

“I saw my mother’s face again, and felt, for the first time, how the stones of the road she had walked on must have bruised her feet. I saw the moonlit road where my father’s brother died. And it brought something else back to me, and carried me past it, I saw my little girl again and felt Isabel’s tears again, and I felt my own tears begin to rise. And I was yet aware that this was only a moment, that the world waited outside, as hungry as a tiger, and that trouble stretched above us, longer than the sky.”

Where’s the bibliography?

Baldwin schools us in how to assess the intensities others have been through. We’re never sure what others have endured or how they privately soar, and so it’s a delight to watch such a skilled writer excavate his characters’ depths. Reading these accounts, we can experience a call to deeper empathy and imaginative intensity.

A little more

- For even more intensity and speculative fiction insight, try Friday Black by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah

- Read more about Baldwin’s work in Poetry

- Dig even deeper into understanding Baldwin’s themes

Become intensely involved with Untold Night and Day by Bae Suah

Intensity can confuse, too. Sometimes it holds us at arm’s length; sometimes we feel privy to an existential whirling outside immediate comprehension that seems freighted with meaning, vital, yet ungraspable. This is the sort of intensity Bae Suah establishes in Untold Night and Day. It’s called a “metaphysical detective story”; it’s labeled as “disorienting.” And though its meaning may not be crystalline, we need accounts like these, too, I think, because they reflect back our own confusions and uncertainties, which can be immensely intense and bewildering.

Untold Night and Day by Bae Suah

Intensity can exist without comprehension, clearly, and though humans strive to interpret baffling experiences, we often fall short of illumination. Or we find that clarity stubbornly refuses to help. Knowing more isn’t always a solution; being insightful doesn’t always prove sufficient. What then?

Then comes the realm of best guesses, the metaphysical geography of ghosts, religions, superstitions, omens, blurred premonitions, witchiness, enchantments, and icks, the things we feel fluttering in crepuscular times but cannot trap or slide under a microscope of apprehension.

“Ayami was her future self or her past self. And she was both, existing at the same time. In that other world, she was both the chicken and the old woman. That was the secret of night and day existing simultaneously. Ayami discovered this through a single movement, bending down to pick up the pebble. And, remembering this simultaneous existence more vividly than she remembered herself, became unable to remember anything else.”

Where’s the bibliography?

Books such as Untold Night and Day may not explain the kinds of mysteries that trouble us more deeply, but they gesture toward the existence of these mysteries, and that acknowledgement alone may be comforting. You feel, at least, that you are not the only one grasping at things at the periphery of existence without knowing what they mean, and maybe you welcome the chance for these things not to have to mean anything at all.

A little more

- Delve into other novels that are intense in their own ways…Imagine Me Gone by Adam Haslett, Mariana Enriquez’s The Dangers of Smoking in Bed, and The Raw Shark Texts by Steven Hall

- The White Review interviews Bae Suah

- Explore a world of detective-related writing at CrimeReads

And Now for Something Completely Different: The Moviegoer by Walker Percy

In Walker Percy’s sprawl of a novel, a hawk-eyed slacker drifts through a physical and emotional landscape he can’t quite seem to grasp. Though technically talented enough to carve out the life his family expects him to claim, narrator Binx Bolling still manages to remain amorphous. Perhaps he finds refuge in a kind of emotional immaturity; perhaps refusing to fully connect is his defense and rebellion, a refusal to buy into values he doesn’t truly understand or wish to inhabit. Or perhaps he’s simply lazy and unwilling to “do the work” it takes to become a more substantial human.

Languorous sunlight, velvet-dark Louisiana roads, an animated cast of family and friends – Binx lacks for nothing and yet keeps grasping for the thread of meaning in the mundanity of it all. Gifted with the ability to observe keenly, Binx also experiences how observational acuity can distance us from ourselves and those around us. It’s hard to be in the moment when you cannot stop thinking about the moment. His “stuckness” may be a privileged foolishness – many of us, after all, don’t have the luxury of idle musing! Or it may resonate with an unquiet, restlessly seeking piece of yourself that turns and turns inside, like a dog trying to make a nest from an obdurate blanket. Troubling.

The Moviegoer by Walker Percy

Some readers knock the narrator’s lassitude and lack of true precarity, but I think his mindset can be accessed by many, regardless of class. Feeling uncertain and unmoored, after all, can strike any of us, and suspecting that you stand just outside the periphery of your “real,” purposeful life is more common than we might wish.

What if all you ever are is potential? Luminous, then unrealized, then ash? A soul-shaking prospect, the kind of thing that can turn a sunny afternoon into an exercise in queasiness. You may not sympathize with Binx’s hedonism or deliberate lack of direction, but you can still enjoy Percy’s lazily intense prose and his depiction of what you stand to lose when you just don’t want to “grow up,” whatever that means.

“It is not a bad thing to settle for the Little Way, not the big search for the big happiness but the sad little happiness of drinks and kisses, a good little car and a warm deep thigh.”

Can life consist of floating along, a kind of river-tubing affair? Does one truly need a Bigger Purpose? Is a Bartleby-like refusal to engage with reality a sign of sophistication, a marker of immaturity, or both? Percy lets us glimpse multiple ways to interpret a life that just isn’t gelling. I find this liberating because it acknowledges the struggle of conforming to expectations while also not completely letting Binx off the hook of social responsibility.

Where’s the bibliotherapy?

It can be comforting to realize shared insecurities, to recognize a shared, un-anchored condition in someone else. And it can be illuminating to witness a character’s attempt to grasp for a meaning that feel elusive. We are responsible, neuroscience indicates, for assigning our own meaning to our experiences. This realization can be sobering or liberating, depending on what you choose to do with it.

- Read a Paris Review interview with Walker Percy

- Or consider a different version of “not being ambitious” with Sayaka Murata’s Convenience Store Woman: A Novel (if you want super intense slackerdom, try another novel of hers, Earthlings)

- Or wander the south with the musical road trip Searching for the Wrong-Eyed Jesus