If there is anything writing orbits, it’s memories. That makes sense – revelatory writing often concerns something that had already happened. Something has been experienced, therefore known, and now the mind can chew on it. I’ve always found memory a bit sticky and off putting, however. For one thing, it’s not immutable. It changes when you’re not looking; it wavers and gets shifty, like entering a familiar room, only to find the furniture rearranged and an off-kilter feel in the air.

We cling to memory, I think, because it can be shared. Memories are the silken threads that tie us together. They’re the stuff of mutual understanding; they fasten us within community and tell us who we are. Mental mirrors, if you will. Writers love this, and can base entire books and careers on the lure of memory (recall Kazuo Ishiguro, for example, and how integral memory is to his plots). There’s a self-importance and sense of menace to certain memories though, or at least to the practice of remembering obsessively. If you do not make space for fresh memories, you become handcuffed to the old ones, fixed in place and identity, not easily able to change. Your memories become more like mummies than living things, and you may ascribe more importance to them than they deserve. You may become afraid of losing them; you may hoard them. You may, like a friend I know, push the same memories over and over on people, leaving no room for their own recollections because you are so afraid that these precious things will vanish along with the best of you if they’re not repeated frequently. Are you sure you control your memories, however? Can you actually remember?

“I think it is all a matter of love; the more you love a memory the stronger and stranger it becomes”

vladimir nabokov

Memory is like Loki, like Coyote. It plays pranks and yanks out rugs. The way our minds treat memories seems stable, like a set of august portraits hung in the family hallway. Time blurs these memories though; entirely new memories can sprout that have no basis in fact at all. Memories can be implanted, can morph, can travel into your brain like seeds on the tides. You can lay claim to another person’s memories and mean it, but still be wrong. You can swear before a court of law to the details of a vivid robbery, yet still be incorrect.

Memories are scrawled quickly on the brain, and not all details stick. No matter, for the mind will go ahead and fill in plausible recollections based on its knowledge of similar things, plus its biases. To make you feel better about yourself, it will often tweak facts in your favor. Conversely, if you’re in the grip of trauma or depression, your memories can easily warp–you’ll lose perspective on them, and they’ll seem like unquestionable dogma, yet will have tip-toed far from facts a long time ago. You can get stuck in them like tar pits, replaying events over and over until you build up a monument that starts to dominate your entire emotional state. Your memories can become flavored by regret or can twist to be what you need to move onward – you may, for example, forget entire stretches of painful time; you may misremember certain events as being sunnier or more scarring than perhaps they actually were. For your memories are not encoded facts. Like most of our thoughts, they’re based on quick impressions, fleeting emotional states, misunderstandings, and more. Memories are our minds hanging on as best they can to interpretations of the past, but these interpretations are inevitably highly personal, colored by temperament and subject to edits and alterations. Dementia shreds them; thousands of them fall through mental cracks during an ordinary day.

Memories can inspire you or hollow you out. They must be handled carefully and with perspective. They cannot always be trusted, or can be trusted more as an expression of inner desires rather than how things actually went down. They’re dismayingly, wonderfully subjective. Without them, we feel unmoored; we lost our stories and our places in time and space. So even though memory is amazingly faulty, it’s the best we have, and so we consider it precious. No wonder it crops up in so many narratives.

5 contemplative books about memory and remembrance

| Title | What stands out | Read this when | |

| Dear Memory by Victoria Chang BUY INDIE | These letters glow with a refined, graceful wisdom it’s worth returning to over and over. Chang doesn’t shy away from either the pangs or the joys of memory. | Your own memories feel worn or stripped of meaning by too much handling. | |

| Out Stealing Horses by Per Pettersen BUY INDIE | Here’s a gentle but biting reverie on recovering memories you thought you’d left frozen back in time. | You know people with buried life stories, or have one yourself. |

| The Bone Woman by Clea Koff BUY INDIE | Move past the memories of living people, and there are bones that testify. Koff doesn’t shield us from the rigor of working day after day with the bones of those killed in wars and genocides, but neither does she spare us from the hard wonders of building a truer account of history. | You want to consider memory from a new angle: that of people now unable to tell their stories directly who depend on careful professionals to testify for them. | |

| The Neuroscience of Memory by Sherrie D. All BUY INDIE | This is a book for those worried about memory slippages and slidings. For reassurance, follow the guidance here to prevent memory issues as much as possible while promoting sharp recall. | You’d like to peer into the neuroscience of how memories are made and preserved. | |

| Memory Wall by Anthony Doerr BUY INDIE | Here we have a collection of short stories that orbit memory and reflect how memories twist, change, and get slippery. | You’d like bite-sized memories from elsewhere. |

Reassembling family memories with Dear Memory by Victoria Chang

Sometimes memories swim along right under the surface of consciousness like koi fish in a pond. Other times, they dive deeper and become more elusive. Maybe you, like poet Victoria Chang, have holes or absences where you wish there was a more solid memory? Families and entire cultures can lose their memories, sometimes because it’s too painful to keep the past in mind, or sometimes to shield others. Memory, after all, can be a kind of curse, and parents don’t always want their children and grandchildren to know what they’d survived. Bad enough, they may reason, that bad memories can be passed down biologically in terms of stress sensitivities.

Dear Memory by Victoria Chang

Here Chang tries to stick memories together into literal collages, filing in the blanks of echoing emptiness where her parents are reluctant to share. Her poems, visual musings, and recollections are rearranged and rearranged, searching for meaningful clues. For some, memories serve as anchors, and lacking them can feel rootless. What then? You may not belong; you may not know how you fit into the trajectory of your ancestors. This is familiar territory for many of us in the U.S. who descended from grandparents and great grandparents who have lost or concealed so many stories along the way, leaving us with a nostalgia for stories we’ve never heard told. There is, of course, the feeling of being too tightly held by culture and its strictures, but there is also the drifting loneliness of knowing yourself unable to lay claim to family memories.

Where’s the bibliography?

Watching Chang reassemble her past is relatable, and may inspire you to do the same. Maybe you can gather heirlooms, scraps of recollections from various relatives, or at least a glimmering of the past gleaned from genetic tracing sites. Be prepared, however, for sour realizations, too. Looking back, you could find slave owners and murderers, rapists and raveners. You could find that, in the great churn to survive, your ancestors have hurt others. You may need to reconcile with who you’re descended from, how hurt scarred them, and how to evaluate who you are now.

As you excavate the past, remember that it, too, has changed. It has morphed; it’s not the same creature it was back then. It’s going to be impossible to fully know, and you cannot surrender yourself to it entirely. Have a sense of tenderness for it, then, just as you hold tenderness for yourself. You may need to enter family or solo therapy to work through particular memories and wound; you may wish to evaluate the kinds of memories you’re currently making.

Overall, it may be best to see memory as something like money: you spend the currency of time on certain experiences, just as you spend money on particular possessions. Then you have them – and are they worth it? Memories of happiness can buoy you throughout life, enriching your quiet moments of reflection, while misspent time can haunt you. Think what kind of memories you would like your children and grandchildren to uncover about you, or consider what pieces of your life you’d like to leave behind for others to uncover.

If you’re feeling shaky right now, you could write yourself a letter. Just as Chang explores letters as a way to convey memory, you could create a memory right now, like an insect in amber, for your future self. What would you like your future self to know about how you are now? Write it down. Open it in a year or three.

A little more

- Follow these directions for how to write a letter to yourself

- Traumatic experiences can make it difficult to really remember what happened – find out why

- Watch a discussion between Victoria Chang and Kristen Keane, both writers who write about grief and memory

- Stephanie Foo writes about memory and familial trauma in her memoir about complex PTSD, What My Bones Know

- If the epistolary form is for you, you may also enjoy Gilead, Marilynne Robinson’s novel in letters about a wayward son, or On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, Ocean Vuong’s novel of letters to an illiterate mother

Stumble into surpressed memories with Out Stealing Horses by Per Pettersen

In Pettersen’s small, subdued earthquake of a book, a memory sprouts one day like a mushroom. Then another, and another, until a whole linked ecosystem of them surround the narrator. Memories do that, making our minds minefields or meadows, depending on what’s stored down there under the substrate.

“People like it when you tell them things, in suitable portions, in a modest, intimate tone, and they think they know you, but they do not, they know _about_ you, for what they are let in on are facts, not feelings, not what your opinion is about anything at all, not how what has happened to you and how all the decisions you have made have turned you into who you are. What they do is they fill in with their own feelings and opinions and assumptions, and they compose a new life which has precious little to do with yours, and that lets you off the hook. No-one can touch you unless you yourself want them to.”

Out Stealing Horses by Per Pettersen

The mind excels at suppressing what it doesn’t really want to know, and there are many reasons for that. For many of us, mulling over horrific things impedes us, crumples us, and can plunge us into extreme depression or anxiety. Powerful memories have the ability to shred our sense of cohesiveness. That’s why grief-work – the process of adequately grieving losses and what-might-have-beens – matters for us humans, stuck as we are in time, unable to shuttle backward except in memories, which we cannot fully depend upon.

Grief-work is what Pettersen’s narrator, Trond, needs to do, even though he is understandably reluctant. He comes across as a wannabe Stoic, a kind of a self-sufficient bear in his cabin, but as the novel progresses, we see how memory turned him into something armored and vulnerable, far from the cheerful boy he used to be. If he remembers long and hard enough, will he be able to swerve out of avoidance into healthier ways of remembering that connect him to fellowship as well?

Where’s the bibliography?

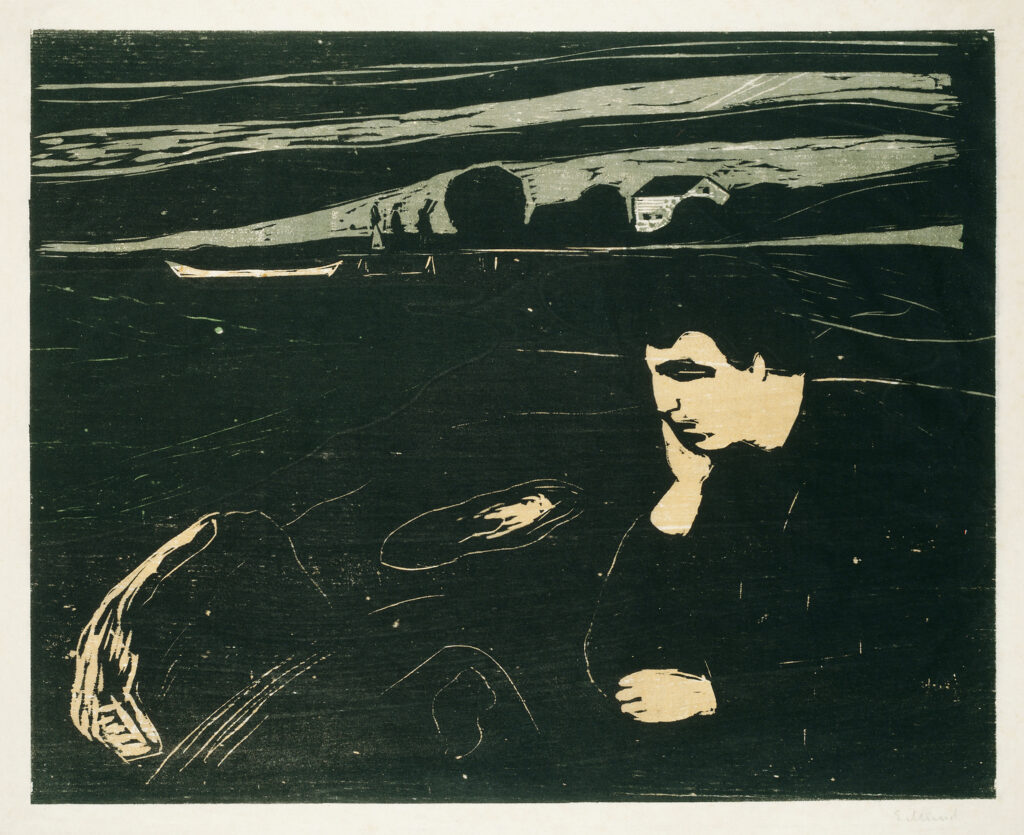

Clearly, much of what writers write about is sad. If not downright crushing. Why this pull toward unpleasant, even tragic memories, and why would we readers want to read about them?

Maybe we want to practice how grief and loss feel without needing to undergo it firsthand; perhaps we wish to feel somehow uplifted at another’s grief, knowing it is not ours. Stories, after all, are mental jungle gyms that let us work out our sense of empathy and our appreciation for what we can learn from others’ narratives. Stories are instruction manuals, just as they are candles flickering in the night to keep us company.

Tragic stories may be difficult to read, but they do round out our understanding of life. We are almost always going to have to shoulder some kind of loss at some point, and some of those losses will be severe. Will we be able to cope? Tragic novels show us that, in some fashion or other, we can. They also help us locate a sense of meaning in the midst of disaster and ruin, what researcher Eva Marie Kooper calls an eudaimonic motive. Yes, our sad memories hurt us over and over, but yes, they also change and can, over time, connect us to others and to our overall life.

A little more

- Nora McInerny addresses how we never truly “get over” those who are gone

- Other books: A River Runs Through It, The Sweet Hereafter, Late Fragments

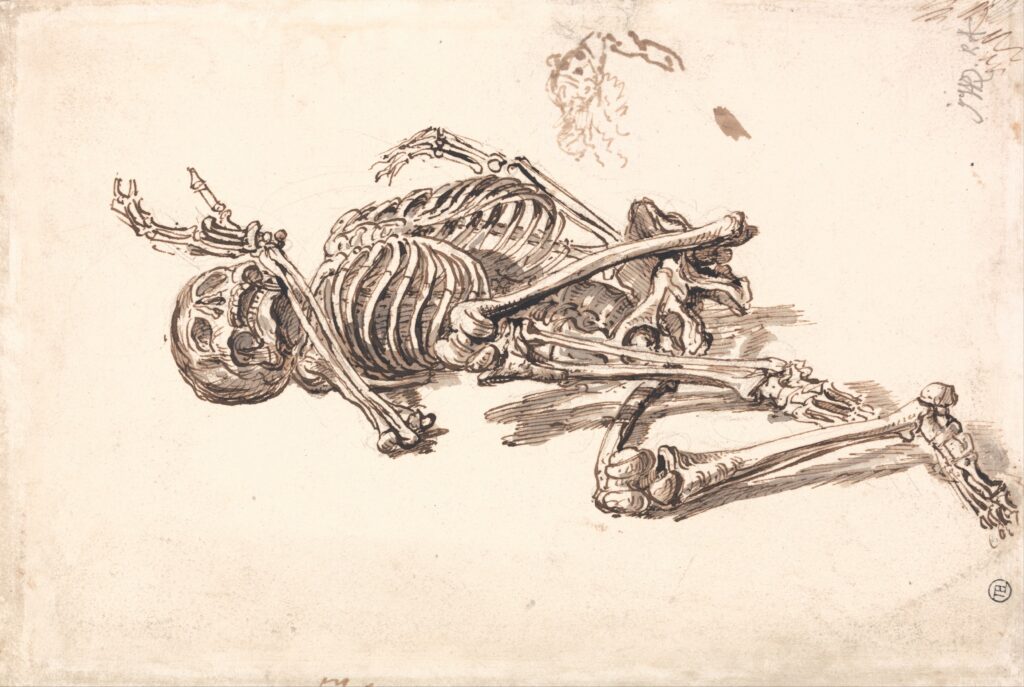

Exhume hidden histories with The Bone Woman by Clea Koff

For many of us, memory remains an intangible thing. For forensic anthropologist Clea Koff, memories have weight and stench. They wear tattered clothes and have entangled limbs and mouths full of mud. From Rwanda to Kosovo, Koff has dug up the bodies that attest to genocide, murder, and other horrific events.

A book like this cannot be an easy read, and Koff does not spare us. What good can it do, one sometimes wonders, to uncover the ten thousandth set of skeletal remains testifying to what never should have happened? Does the ten thousand and first set somehow add yet more pathos and meaning? When is enough enough?

The Bone Woman by Clea Koff

Words like Koff’s seem to have their own smell and pungency, one that will follow you into your dreams and puncture your happier moments. Yet you will also feel witness to Koff’s remarkable sense of purpose and will have to face the importance of relics, particularly human remains, in helping us piece together events a government didn’t want remembered.

“Put those national institutions under the magnifying glass, I challenged the class. Take a closer look, not just because those institutions have denied illegal activities of which we now have clear evidence, but also because the bodies unearthed from supposedly different conflicts have told such similar stories. For example, Rwanda has been described as having experienced “spontaneous tribal violence” in 1994, while the former Yugoslavia was said to have experienced “war” between supposedly discrete “ethnic and religious” groups from 1991 to 1995. How could such different conflicts produce dead who tell a single story—a story in which internally displaced people gather or are directed to distinct locations before being murdered there? How could “spontaneous violence” or “war” leave physical evidence that reveals tell-tale signs of methodical preparation for mass murder of noncombatants? I’m thinking about countrywide roadblocks to check civilians’ identity cards, supplies of wire and cloth sufficient to blindfold and tie up thousands of people, bodies buried in holes created by heavy earth-moving machinery during times when fuel alone is hard to come by.”

The bodies Koff handles mutely tell us who was thought inconvenient or threatening, who was disposal or hated, forgettable or beyond the pale. In cleaning these bodies and restoring them to their families when possible, Koff asks us to examine tough things and resolve not to keep perpetuating them. It is possible, she cogently explains, for bodies to represent not just inconvenient humans, but also national desires for wealth and power, spelled out in death. We are willing, in short, to do terrible things when we think we can bury our deeds beyond reach of memory or repercussion.

Where’s the bibliography?

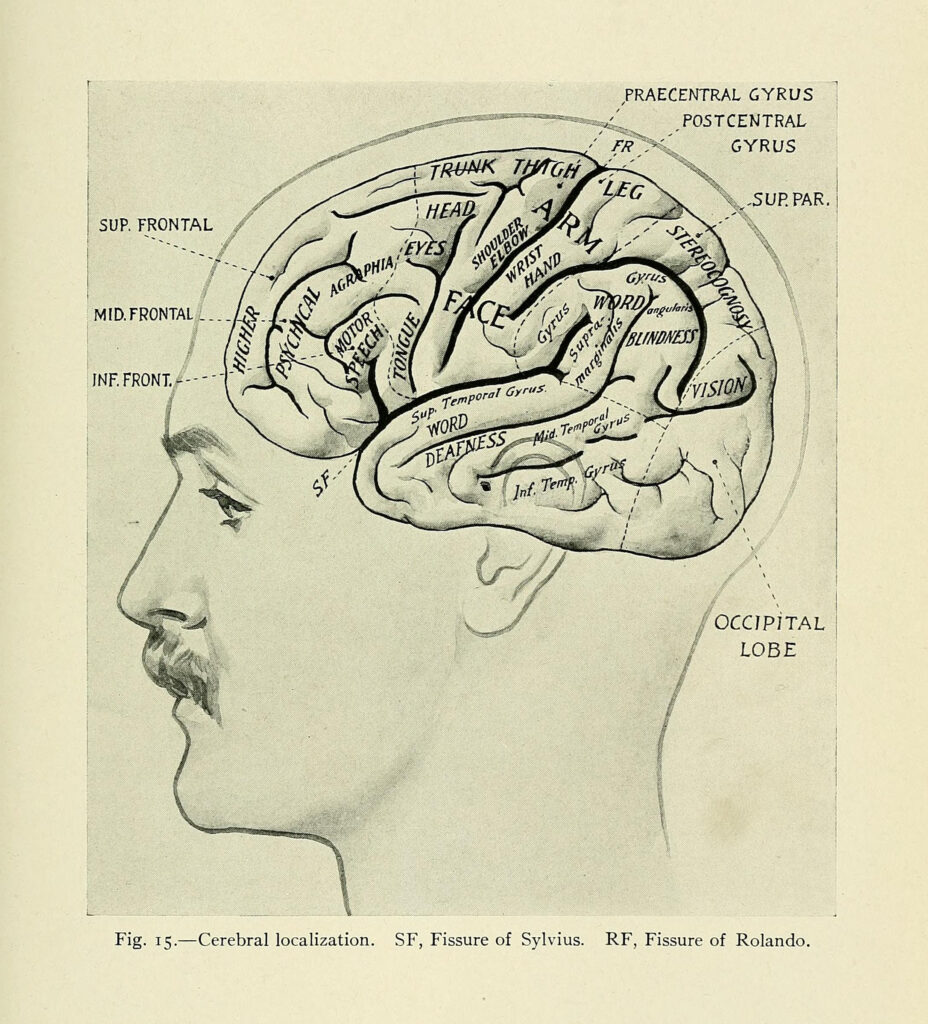

Bodies hold memories in a very embodied way – memories are not simple tenants of the brain, but roam, we are learning, throughout the gut and other cells as well. Collectively, our cells store our individual memories, just as our bodies store narratives about our culture and nation.

Pick up a memory, and you may find it connected to another, just as a bone often remains linked to another. I’m thankful for Koff’s work and for her elegance in describing it, just as I’m thankful to historians who scrape away at tomes and dry repositories, trying to uncover collective remains of narratives that can still impact us today. For me, the bibliotherapy here is not only a deepened sense of how important memory can be, but the importance of seating memory within context, as much as possible. To understand a set of remains or a memory, we need to know as much about the context as possible.

“Why did those governments decide to murder their own people? Why did soldiers and police and barbers and mechanics murder their own neighbors? I think the answer is self-interest. Particular people in a government of a single ideology with effectively no political opponents have supported national institutions that maintain power for themselves. What muddied the waters were the “reasons” the decision makers gave for their political agendas. Take Kosovo: were the killings and expulsions in the 1990s really meant to avenge the Battle of 1389, as Serbian president Slobodan Milošević was fond of stating? Or was it because mineral-rich parts of Kosovo can produce up to $5 billion in annual export income for Serbia? Or take Rwanda: did Hutus kill their neighbors and all their neighbors’ children simply because they were Tutsi, as the government exhorted them to do? Or was it because the government promised Hutus their neighbors’ farmland, land that otherwise could only have been inherited by those very children, and those children’s children, ad infinitum?”

We must also be conscious of what memories we choose to honor and visit. Obscured travesties, such as how the US’s war in Afghanistan, can omit realizations we need to grapple with and can make us think we are nobler than we actually are. Corrected memories and national narratives reground us in greater humility and in the collective determination to establish a common understanding of what occurred and how we were both implicated and impacted.

It’s advisable, then, to examine stories for clues. Is this an accurate story? A valuable one? One you want to ingest and digest, making it part of your cells? It is possible, after all, to share memories, just as it is also possible to reject memories that are overly sticky or clingy, one that want to freeze us in place. It’s a tricky dance, to determine what to remember and for how long. When is a memory sustenance; when is it poison? Is it something to be held close and licked in private, or is it a toxic anchor that won’t let you move forward, something you should hold more loosely and with more respect for the damage it can do?

A little more

- Read an interview with Koff, including her powerful words: “But in working day after day to separately document and exhume each body in the initial grave of almost 500 people, I came to see that genocide is actually made up of many individual murders. Once I saw that, I also began to see the killers as individuals, and then the planners – those key people who provided the strategy and the tools. That contextualization of the crime was very different from my experience of investigating unidentified bodies in the United States, where each case stood alone and was perhaps less likely to spark similar questions of patterns or politics or prevention.”

- Watch Black Earth Rising, a shattering drama series about memory and Rwanda

- Read more about missing people in the US and the efforts to recover their bodies when necessary or more about projects such as Argentina’s Museo ESMA, which restores our knowledge of Argentina’s Dirty War

- Should dark tourism be supported or given a second thought?

- Also read The Nature of Life and Death: Every Body Leaves a Trace and Hades, Argentina

Learn how to sharpen your memory skills with The Neuroscience of Memory by Sherrie D. All

One terrifying aspect of memory is the prospect of losing it. Outside of outright violence, what is as terrifying as Alzheimers, dementia, or a similar condition leaching away your memories?

That’s why I find memory glitches so discomfiting. Sometimes, when grasping for an elusive word or a forgotten name, a kind of existential cobra starts rising from the loosely-woven basket of my brain. Is this it? The sign of impending memory loss? Agh! So I get pulled into books about how to resist memory loss, improve my dulling recollections, and stave off inevitable decay just a little longer.

The Neuroscience of Memory by Sherrie D. All

All’s book gives us readers a fairly straightforward set of recommendations on how to hone memory. Neural connections are not, as we once thought, set in early adulthood and doomed to fraying ever after. New connections can sprout; memory skills can be sharpened. Whew. The possibility of it alone is comforting.

Where’s the bibliography?

Feeling prepared is an excellent tool for dealing with fears, including the fear of memory loss. While I try not to focus on memory-related fears or on contemplating cognitive decline, it would be silly not to take advantage of established strategies. Our brains, after all, are extremely powerful. As a child raised without a TV, I used to compete in memory-based competitions, and could once memorize swaths of text, adding up to thousands of words at a time, with relative ease. I wouldn’t make that claim now, but I do know that our brains do more than we give them credit, sometimes, and that by exercising them in specific ways, we can greatly expand our working memories, ability to recall people’s names, and much more that can help us feel more connected and less likely to spiral into a forgetful fog.

A little more

- Dr. Yewende Pierce discusses how memory works

- Master 11 memory techniques

- Yes, there are Memory Championships!

- If a memory palace is good enough for Sherlock Holmes, it’s probably good enough for you and I. Let’s practice how to use one

- Find out why we forget the books we read

- Also read: Before I Go to Sleep, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, Moonwalking with Einstein, The Art of Memory, Metaphors of Memory

Experience some quick flashbacks with Memory Wall by Anthony Doerr

Doerr is one of those short story writers that inspires vicious and immediate envy. The kind that wakes you up at night and makes you want to throw things. He’s just…excellent. In this collection, he takes memory on, doling out a sampler pack of stories set around the world in various brains.

These stories concern how memory works, both for a person and a country. Memory, as Doerr depicts it, is slippery. Lose a memory, and you’ve virtually lost a childhood, a beloved friend, a hometown. How are we supposed to go on with that kind of threat hanging over us? That’s the struggle Doerr’s characters find themselves in, from grappling with advancing dementia to considering how a culturally important town is about to be submerged. Is it ever a relief to forget? I think so, but I do not wish to forget these stories.

“Memory builds itself without any clean or objective logic: a dot here, another dot here, and plenty of dark spaces in between. What we know is always evolving, always subdividing. Remember a memory often enough and you can create a new memory, the memory of remembering.”

Where’s the bibliography?

In their very brevity, short stories can help us absorb big questions quickly. Like a cold plunge, perhaps. On average, we get 2 billion heartbeats each. That sounds like a lot, and it is. But still, when I know I’m unlikely to remember a mediocre show or even the vaguely satisfied, vaguely discontented way I felt while watching it, I like to ask myself if that hour is a good use of some 4,000 heartbeats I won’t get back.

Time, when sliced this way, gets a little terrifying. There is no easy way to extricate yourself from the raw fact, however, that we are all exchanging heartbeats for memories. This prompts me, as it does Doerr’s characters, to think about memories carefully, to measure out ones I wish to keep and polish while also determining which ones should be laid down, and to hold memory loosely in general, while still honoring what it means for my own fleeting existence.

“Every hour, Robert thinks, all over the globe, an infinite number of memories disappear, whole glowing atlases dragged into graves. But during that same hour children are moving about, surveying territory that seems to them entirely new. They push back the darkness; they scatter memories behind them like bread crumbs. The world is remade.”

A little more

- NPR discusses Memory Wall with Anthony Doerr

- Granta interviews Doerr

- Also read: The Shell Collector, As I Lay Dying, In Search of Lost Time, The Unconsoled, Beloved