Acceptance: the judo twist that can get you moving again

The concept of acceptance is such a chimera. It requires extending grace for things that are galling. Acceptance brings both love and endurance under its umbrella. Tolerance is there too, as is the warmth of inclusion.

But acceptance also holds a sting, that of possible passivity or unjustness. Not everything, after all, can be borne, and it is not necessarily healthy to radiate acceptance toward every intrusion or inequality. What, then, are the ethics of acceptance?

It could depend on your perspective. Do you respond in the moment or take a larger view that lets you put the thing you’re trying so hard to accept into context? It could depend on how you want to feel. Like judo, acceptance is an art that can be practiced. Perhaps you can come to an understanding with it; perhaps you can learn when and how acceptance serves a satisfying life.

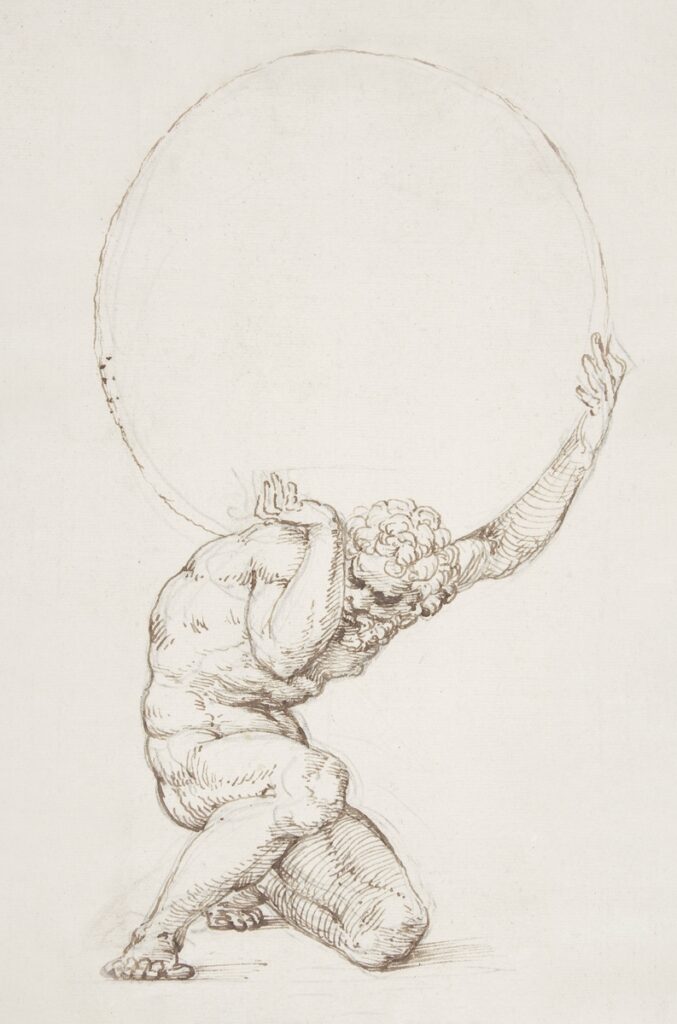

In the poem below, we see the well-known Sisyphus of myth deprive the gods of their pleasure in his punishment by exercising a secret acceptance. After all, poet Stephen Dunn nudges us, acceptance can happen at all levels of life, wherever you happen to find yourself.

Sisyphus’s Acceptance

These days only he could see the rock,

so when he stopped for a bagel

at the bagel store, then for a newspaper

at one of those coin-operated stalls,

he looked like anyone else

on his way to work. Food—

the gods reasoned—

would keep him alive

to suffer, and news of the world

could only make him feel worse.

Let him think he has choices;

he belongs to us.

Rote not ritual, a repetition

which never would mean more

at the end than at the start . . .

Sisyphus pushed his rock

past the aromas of bright flowers,

through the bustling streets

into the plenitude and vacuity,

every arrival the beginning

of a familiar descent. And sleep

was the cruelest respite;

at some murky bottom of himself

the usual muck rising up.

One morning, however, legs hurting,

the sun beating down,

again weighing the quick calm of suicide

against this punishment that passed for life,

Sisyphus smiled.

It was the way a gambler smiles

when he finally decides to fold

in order to stay alive

for another game, a smile

so inward it cannot be seen.

The gods sank back

in their airy chairs. Sisyphus sensed

he’d taken something from them,

more on his own than ever now.

© 2003, Stephen Dunn

From: Poetry, Vol. 181, No. 4, February

Publisher: Poetry, Chicago

5 revealing books on how to extend acceptance

| Title | What stands out | Read this when | |

| Nervous Conditions by Tsitsi Dangarembga | How much compromise can you accept to secure what you thought you wanted? Dangarembga pits her young narrator against this question, as she tries to wrest a decent education from a flawed situation. | You know you’re going to hurt yourself chasing what you think is best for you. | |

| Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro | Haunting and disturbingly given over to memories, Ishiguro’s novel pokes at whether or not hope and care can upend rotten circumstances. Does your life matter if it was never really yours at all? | You’re feeling short-changed or forced to betray your own hard-beating heart. | |

| Far From the Tree by Andrew Solomon | Birth, we sometimes forget, is a roll of the dice, and family is a complicated mish-mash of chance and genes. What happens when your child isn’t who you thought they would be? | You feel you don’t belong or you’re struggling to love people who are close but nonetheless seem strange. | |

| A Kestrel for a Knave by Barry Hines | Pointed straight toward a future in the coal mines, Hine’s narrator turns momentarily toward wilder things instead, if only in the margins and sidelines of his short, brutal years. | You need a dose of feral things to counteract the quiet desperation. | |

| Radical Acceptance by Tara Brach | Despite the flowery cover, here’s a relatively grounded excavation of acceptance and how learning to accept is much more than cynical resignation. | When meditation gives you hives but you still want to focus on something other than your own careening thoughts. |

Nervous Conditions by Tsitsi Dangarembga

A coming-of-age novel, Nervous Conditions asks how you are supposed to accept your own ambitions when you are stuck in a bad system. How do you seize and hang onto slippery, limited opportunities; how do you deal with systematic oppression reaching through the bodies of your friends and family members to hold you down and choke you?

“Quietly, unobtrusively and extremely fitfully, something in my mind began to assert itself, to question things and refuse to be brainwashed, bringing me to this time when I can set down this story. It was a long and painful process for me, that process of expansion.”

The problem of not being given enough of a chance is a huge one. Reading Nervous Conditions, your heart goes out to Tambu, a Zimbabwean girl trying to learn in a land where education belongs to men. As she struggles, Tambu starts to wonder how she can bear to accept her country, her society, her family, and even herself. It’s a book about how what you permit and what you refuse swallow both shape you; it’s also about how life imposes limitations too big to overcome alone and how growth can also involve amputation.

“Nyasha knew nothing about leaving. She had only been taken to places – to the mission, to England, back to the mission. She did not know what essential parts of you stayed behind no matter how violently you tried to dislodge them in order to take them with you.”

It is not so easy to cast off one’s heritage, not so easy to extricate oneself from limitations, even when you don’t accept them. What to do? It is possible, sadly, to love your people and your home but to not accept them or to feel accepted by them.

Where’s the bibliotherapy?

Tambu demonstrates appropriate acceptance of what’s happening in her life by being clear-eyed and realistic. When an opportunity occurs, she takes it, and when that doesn’t prove to be ideal, she adjusts. She also refuses to accept inequality, even if she cannot fix that inequality herself and even if it will continue to hurt her. Emulate her by:

- Consider what’s going on in your life. Are you being realistic about it or do you have a “filter” of desire, expectation, or bias over the facts that could be leading to a misinterpretation?

- Pick one small, realistic change you can make that will improve what’s going on

- Check in with your principles. Are you changing in ways that fit your ideals? If not, readjust.

Read “Nervous Conditions” when:

You’re struggling to decide what pieces of yourself to tend and which to sever. Or when you know you’re up against forces much bigger and more ephemeral, and you just want to live.

Savor the foggy wistfulness of Never Let Me Go

Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro

You’re going to see this one on dozens of recommended reading lists. Much as I’m trying to feature less recognized works, it’s difficult to skip a book so full of facets worth contemplating.

In his trademark measured prose, Ishiguro conjures up a cozily recognizable British setting complete with boarding schools, cups of gently steaming tea, and copious reminiscing. The coziness stops at organ harvesting, however, and the reminiscences are jarringly dedicated to the gaunt years his characters were given before being forced to yield up various organs.

Clones of adult citizens, his characters are essentially farm stock, treated with some kindness, but always penned in non-momentous lives and always pointed toward the abattoir. Kathy, the narrator, is a somewhat defensively dreamy woman who clings to the notion that her former classmates’ lives are not being truncated in vain, that the memories they made during their boarding school years are sufficiently buoyant to carry them throughout the rest of their lives, and that the classroom art they were encouraged to produce could somehow prove meaningful or even salvatory.

“I can see,’ Miss Emily said, ‘that it might look as though you were simply pawns in a game. It can certainly be looked at like that. But think of it. You were lucky pawns. There was a certain climate and now it’s gone. You have to accept that sometimes that’s how things happen in the world. People’s opinions, their feelings, they go one way, then the other. It just so happens you grew up at a certain point in this process.’

‘It might be just some trend that came and went,’ I said. ‘But for us, it’s our life.”

For Ishiguro, memories may constitute our essence. But how do we come to grips with lives that are unjustly truncated or memories that provide only scanty sustenance? As the science of memory demonstrates [*LINK], memories are not always snug, dependable mental cottages – instead, they shift, mutate, and confabulate in undermining ways. Where does that leave you?

Well, you can still have friendships and love, Never Let Me Go insists. Part of the novel’s poignancy stems from how it depicts acceptance – though Kathy knows love can only go so far, for example, she still treats her classmates with tenderness, accepting their shortcomings.

“And what made these heart-to-hearts possible–you might even say what made the whole friendship possible during that time–was this understanding we had that anything we told each other during these moments would be treated with careful respect: that we’d honor confidences, and that no matter how much we rowed, we wouldn’t use against each other anything we’d talked about during those sessions.”

Acceptance of each other, then, even if you cannot fully accept death or an impending end, offers a way to cope. But if we are to believe Ishiguro, love involves manipulation and deceit, too.

“When you become a parent, or a teacher, you turn into a manager of this whole system,” the author stated in an interview with The Guardian. “You become the person controlling the bubble of innocence around a child, regulating it. All children have to be deceived if they are to grow up without trauma.”

Is that, however, a truly noble aim? We do our best to avoid trauma and pain, striving to protect those we love from pain, yet in doing so we may do grievous damage. Just as protecting each other too assiduously from germs and contamination can result in immunological problems, over-protection can crumple a soul, too, I think. Wouldn’t it be better to be taught how to deal with adversity than how to avoid it altogether?

For me, one of the novel’s central questions becomes how to handle harm in a healthy way and how to make ethical choices when much of our happiness and fulfillment is based on others’ sacrifices. Issues of acceptance are woven all through a question like that.

Where’s the bibliotherapy?

In the book, Kathy and the other donors face a tremendous amount of uncertainty about what their memories and the rest of their lives add up to. They try to make sense of these uncertainties while also needing to reconcile themselves to dying young.

For uncertainty, narrative therapy offers direction that, in brief, boils down to:

- Explore your life narratives

- Find and label narratives that present problems

- Rewrite the narrative

For Kathy, one prevailing life narrative is: “If I try hard enough to connect the dots, I can make sense of what’s happening.” As the story goes on, however, it becomes clear that a sensible narrative just isn’t going to emerge. Kathy could instead rewrite her narrative to something along the lines of: “I may not find the meaning I want, but I can decide that my life was still meaningful to me.”

Do you think narrative therapy could help you reinterpret some of your prevailing narratives?

Read “Never Let Me Go” when:

It’s a misty day and you want to step into someone else’s memories. Or when you feel boxed in and compelled to get by without enough choices or joy.

A little more

- Read more about the malleability of memory in the Smithsonian article “How Our Brains Make Memories”

- Listen to Depeche Mode sing “Never Let Me Go” (or to Florence + the Machine’s version)

- Watch the movie version of the book, directed by Mark Romanek

- A Japanese TV series also exists

- Sign up to be an organ donation

- For a gorgeously grittier and more everyday depiction of acceptance, read Lucia Berlin’s A Manual for Cleaning Women

Better accept family with Far From the Tree

Far From the Tree by Andrew Solomon

A big part of growing up is accepting and growing through and past what our parents did to us. Sadly, I think most of us experience chinks and chasms while growing up where we would have wished for more support, less judgment, more kindness and less indifference to our unique needs. Just as our parents likely craved recognition, too, and guidance on how to do a good job. There is, of course, no possible way to be a perfect parent or a perfect child. Yet we can learn ways to reconcile ourselves to our experiences of family.

“Perhaps the immutable error of parenthood is that we give our children what we wanted, whether they want it or not. We heal our wounds with the love we wish we’d received, but are often blind to the wounds we inflict.”

Weighing in at over 700 pages, Andrew Solomon’s book on unique families and universal acceptance might strain your wrists, but may also enrich your soul. By interviewing the parents of exceptional children, Solomon sifts through stories about families with exceptional children for guidance on how to accept his parents’ decisions and steer his own family in turn.

Far From the Tree is far from a perfect book – criticisms include that most of the families Solomon interviews are privileged, that Solomon does not sufficiently plumb varying experiences, that he is prey to his own biases, and that he overgeneralizes in his yearning to discover universality in the hurly-burly tumble of being human. I’m very open to those criticisms and admit that his equivalencies do not always ring true (and can even be markedly offensive).

What stood out, though, was how the books dragged bitter truths that make us uncomfortable to the conversational surface. Must parents always love their children? Unconditionally? How far can they go to improve their children’s lot in life, or to make their children easier to be around? In the biological muck of being related there can be real suffering, which I think is useful to acknowledge.

Where’s the bibliotherapy?

For reconciling yourself with difficult family dynamics, family systems therapy might help. That’s a kind of therapy that addresses not just you as an individual, but you as a member of a larger network of relationships that shape you.

Far From the Tree demonstrates family members learning to accept each other. Part of this acceptance involves learning to:

- See your family members for who they are (and not necessarily who you want them to be or hope they could be)

- Sit with what is uncomfortable. Can you get used to it? Can you find a new way to see this person?

- Is there anything about yourself and your own expectations you can shift to make the dynamic better for everyone?

What else do you observe in the families being interviewed?

Read this when

You want to catch a glimpse of other lives and other struggles. Or when you want to learn from other families how to handle your own.

A little more:

- Far from the Tree documentary:

- The National Organization for Rare Diseases

- This Conversation article on caring for children with complex needs

- Positive Psychology discusses healthy boundaries

- Andrew Solomon’s book site

Fly high in hard times with a Kestrel for a Knave

A Kestrel for a Knave by Barry Hines

Sometimes acceptance from other humans is too much to hope for. Often, animals step into the gap to offer the acceptance we crave. It can be easier, somehow, to have a wordless relationship with a feathered or furred being than a naked, hairy one such as ourselves.

Billy Casper, the protagonist of Barry Hines’s short, lovely, and brutal book about growing up tough, would likely agree. Bullied by others and buffeted by mining-town life, Billy turns toward a kestrel instead, discovering a feral bond that benefits them both while still permitting some of their individual wildness to survive.

“It’s fierce, an’ it’s wild, an’ it’s not bothered about anybody, not even about me right. And that’s why it’s great.”

Billy finds relief in learning to hunt with the hawk he calls Kes. Nature itself is another refuge. For me, this book is about finding acceptance in things that cannot actively accept you, a paradox that is nonetheless true to life. When we’re craving acceptance, cordial indifference sometimes feels ideal. It pulls us out of ourselves and helps us focus on experiences happening outside our own skins, which can be a huge relief.

When you cannot accept the direction in which your life is headed, spending time in nature and seeking out animals is not the worst thing you can do, even if that, too, will eventually break your heart. But some ways of being broken are better than others, I think Hines is saying, and in his story, I find balm for feeling out of place. I could be stretching the lesson, but I also see a glimmer of instruction in the choices Billy makes of how to find beauty in bereftness. Rather than cause yet more hurt, he chooses to connect and in that way chooses flying over falling.

Where’s the bibliotherapy?

As someone dealing with ongoing trauma, Billy uses creativity in connecting with nature and with Kes. To do this, he had to:

- Shift his attention off his own emotional agony

- Become curious about a different being (Kes)

- Allow a new dynamic to unfold without trying to control it completely

What else do you find in the book to guide or inspire you? Are there ways you could emulate Billy?

Read A Kestrel for a Knave when

There’s a cold little wind howling through your soul. Or for when you’d like to fly into a slightly different time and place that’s rife with both rejection and gritty insight.

A little more:

- The trailer for Kes, the 1969 movie adaptation

- A Kestrel for a Knave radio dramatization

- Thames TV interviews Barry Hines

Stretch yourself with Radical Acceptance

Radical Acceptance by Tara Brach

I struggle pretty much every day with stubborn, cantankerous emotions. It feels like running through the woods, getting whipped across the face by thin branches or needled by clinging blackberry vines. More than is actually helpful, I hear a sharply critical voice muttering away in my brain, and can’t always flow with the uncomfortable thoughts and feelings that, like gravel in my shoe, make it tough to go on. Why can’t things be a little easier, a little freer from sticky imperfections? Why am I so often finding conditions wanting, a state of being Dr. Tara Brach calls “resistance to reality”?

“Perhaps the biggest tragedy of our lives is that freedom is possible, yet we can pass our years trapped in the same old patterns…We may want to love other people without holding back, to feel authentic, to breathe in the beauty around us, to dance and sing. Yet each day we listen to inner voices that keep our life small.”

Acceptance is tough – on the one hand, you want to excel; you want to do well, help others, and do so with competence and aplomb. On the other, you want to roll with mistakes, recognize them for the usually momentary speed bumps they usually are, and move on without mulling it over. And sometimes you just want to let yourself be a mess.

Books like Dr. Brach’s aren’t magic pills – they don’t automatically ease the heart or quiet the brain. Along with steady practice though, they help. They outline trailheads we can follow to become more accepting of ourselves, of others, and of prevailing conditions and the ambient “ick” of the world.

In her work, Tara explains how to notice the precursors to rejection. Tense shoulders, an urge to evaporate, mounting anger … .if we catch these indicators in time with mindfulness, we can avoid knee-jerk coping mechanisms that don’t serve us well.

Second, Tara advises practicing acceptance. By ‘radical’ she does not mean sending a silent ‘yes’ to whatever ish happens to be unfurling, but rather a clear-eyed acknowledgment that matters are not as you might wish, that you cannot flip a switch and change them, and that accepting this frees you up to deal with whatever comes next more productively.

Like me, you, too, might often feel rubbed the wrong way by self-help books. This one may not be for you – admittedly, the language can get vague, and at times I would appreciate the inclusion of more rigorous neuroscience. Nevertheless, it’s unlikely a single book could offer everything needed, and I get the sense that acceptance is a life-long endeavor that will involve many books, many poems, many bruised ego knees, and many “try again” moments.

Read “Radical Acceptance” when

You’d benefit from a kind voice on your side. Or when you’re tired of bristling against everything that’s bothering you.

A little more:

- One place to begin with Buddhism, which teaches acceptance, is Lion’s Roar; it includes a reading list of Buddhist classics

- The Buddhist Society

- Acceptance and Commitment therapy, which provides instruction on how acceptance helps one take action.